Understanding and using the limits of our memory

There was once a time that the phone company was the most powerful purveyor of information technology and research. The venerable Bell Labs employed thousands of people doing primary research, in exchange for their monopoly status as the only phone carrier.

In 1956 (a very good year, BTW) Psychologist George Miller published a paper entitled, The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information.[1]. He had been tasked to empirically find how many random digits a person could remember at any one time so Ma Bell could figure out how many numbers to use for defining the concept of the telephone number. It tuned out most people can only remember 5-9 things at any given time with resorting to tricks, such as chunking. This is sometimes referred to as working memory and its contents are typically lost within 20 seconds without some sort of active rehearsal.

This fact alone has significance for people who create presentations, visualizations, instruction, and almost any kind of media. If people can only keep a limited amount of information at any given time and you want them to follow what you’re showing, you have to manage which of those seven items should be top-of-mind at any given time.

The research into memory and perception of information got a bit more nuanced as time went on. In 1988, John Sweller extended Miller’s observations and applied them to instruction. His Cognitive Load theory suggested that memory is comprised of two primary structures— short term and long term— both of which are controlled by a central executive (our explicit attention- an even more precious commodity of one). Long-term memory is where instruction goes once it is actually learned by the use. In that sense, the aim of all instruction is to alter long-term memory, but information must first pass through short-term memory first. [2]

Sweller viewed long-term memory as “sophisticated structures that permit us to perceive, think, and solve problems,” rather than a group of rote-learned factoid and these structures are chunked into things called schemas that organize a group individual facts into a single element, where they only take up one slot of the precious seven in short-term memory.

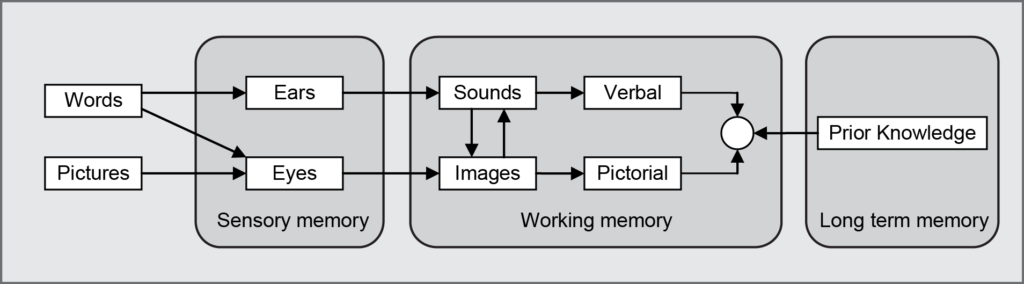

Richard Mayer’s later work in Multimedia Learning studied the effects of combining various forms of media and its effects on understanding. He proposed that we have two primary pathways for sensing information (called the Dual-Coding theory), an auditory path, which takes information from the ears, and a visual path, which takes information from the eyes.

The distinction gets fuzzy when reading is involved. Even though words are processed by the eyes initially, the internal mechanisms of the auditory path are used to make sense of the words. Coupled with the fact that we have a limited number of things we can focus on at any given time, care needs to be taken to keep from overloading a single pathway with too much information.

Having two pathways doubles the amount of information that is in play at any given time, but it can be tricky to connect the right kind of information to the right pathway to maximize the amount of communication. Written words complicate this even further because they involve both channels. This is why putting a lot of text in PowerPoint slides will dramatically compete with the spoken words for the audience’s attention. [3]

One of the primary goals of information communication of any kind is to present information in a comprehensible manner. Designers must respect the limitations and make use of people’s ability to accept information in order to reach that goal.

Researchers have proposed that we have two primary pathways for sensing information, an auditory path, which takes information from the ears, and a visual path, which takes information from the eyes. The distinction gets fuzzy when reading is involved because even though words are processed by the eyes initially, the internal mechanisms of the auditory path are used to make sense of the words. Coupled with the fact that we have a limited number of things we can focus on at any given time, care needs to be taken to keep from overloading a single pathway with too much information.

Having two pathways doubles the amount of information that is in play at any given time, but it can be tricky to connect the right kind of information to the right pathway to maximize the amount of communication. Written words complicate this even further because they involve both channels. This is why putting a lot of text in PowerPoint slides will dramatically compete with the spoken words for the audience’s attention.

One of the primary goals of information communication of any kind is to present information in a comprehensible manner. Designers must respect the limitations and make use of people’s ability to accept information in order to reach that goal.

About Bill Ferster

Bill Ferster is a research professor at the University of Virginia and a technology consultant for organizations using web-applications for ed-tech, data visualization, and digital media. He is the author of Sage on the Screen (2016, Johns Hopkins), Teaching Machines (2014, Johns Hopkins), and Interactive Visualization (2012, MIT Press), and has founded a number of high-technology startups in past lives. For more information, see www.stagetools.com/bill.

Notes:

[1] Miller, G.. (1956). “The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information”. Psychological Review. 63 (2): 81–97.

[2] Sweller, J., Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning, Cognitive Science, 12, 257-285 (1988).

[3] Mayer, R. (2005). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In R. Mayer, (Ed.) Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.